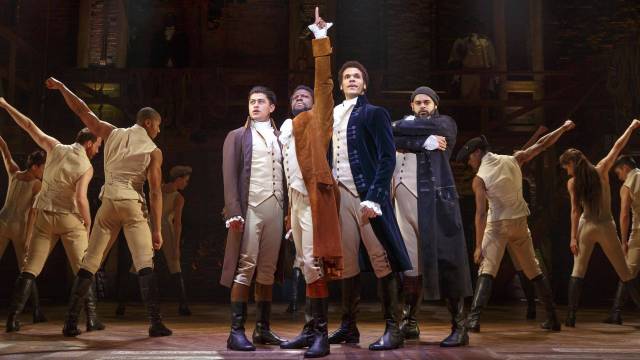

Michael Luwoye and the company of the Hamilton national tour. (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Four songs into the massive theatrical phenomenon Hamilton, when the Schuyler sisters sing about the excitement of being alive in a time of great ferment and hope, I was overcome by the undeniable immensity of what I was seeing. A theater packed with a diverse audience was watching the descendants of slaves, immigrants, and indigenous peoples retell and reclaim the American story. The house was enraptured by a musical that had no reliance on outlandish effects or impressive scenery but on a large, ferociously talented cast of actors—the very best kind of special effect. Later on, the spectacularly staged Battle of Yorktown, a masterfully directed Brechtian sequence using only rap, song, and dance, brought prolonged, enthusiastic applause. Here was an audience responding to the theatricality of what they were seeing, the undeniable immediacy of being in the same space as a group of performers palpably excited to be giving everything to this show at this time to this crowd. (Although there are lead roles, Hamilton is undeniably an ensemble piece.) The vast number of triple-threat players, their energy, the precise choreography they execute so flawlessly, the hip-hop aura that connects past to present—it’s no wonder audiences are thrilling to this piece.

Writer and composer Lin-Manuel Miranda’s reconception of the birth of the United States of America using actors of color as the founding fathers is an undeniably subversive and compelling idea. (Miranda was inspired by Ron Chernow’s lengthy, impressive, and eminently readable biography of Hamilton.) And with Andy Blankenbuehler’s dynamic choreography and Thomas Kail’s brilliant staging, Hamilton is undeniably an achievement.

The company of the ‘Hamilton’ national tour. (Photo: Joan Marcus)

But as the evening goes on, it’s clear that Miranda wants to do more than just dazzle audiences with virtuosic theatricality, he also wants to create a living portrait of a man both equal and unequal to his times (as are we all, in hugely varying degrees). He wants to create a human being out of the myth and distance of history, and he wants the audience to believe in and feel for that human being. To do so, he turns from the distancing techniques of Brecht toward the conventions of the modern romantic American musical, and he’s unfortunately far less successful in that endeavor. Miranda turns away from the clash of ego and ideas that make up politics to focus on Hamilton’s personal tragedies (namely a sex scandal and the death of his son), giving more time to Hamilton’s wife Eliza, and the piece falls into the melodramatic and the maudlin. The hip-hop aspects of the score recede, and we revert to standard, somewhat bland, Broadway pop ballads. The songs aren’t very memorable (although they’re performed with commitment), and the show begins to feel more connected to Les Miz and other modern pop spectacles than to either American history or hip-hop culture. And neither Alexander nor Eliza fully comes to life. We see the events in their lives but their responses to those events, their songs, lack resonance, and the audience responds with pity rather than compassion.

After Eliza is humiliated by Hamilton’s public confession of an extra-marital affair (which he is driven to by charges of financial impropriety), her song “Burn” features the line “I’m erasing myself from the narrative.” The post-modern phrasing feels grad-schoolish and overly intellectual, rather than a cry of devastation. (As Eliza, Solea Pfeiffer conveys the anguish the song lacks.) When Hamilton’s son dies in a duel (foreshadowing his own death), he sings to Eliza, “If I could trade his life for mine/He’d be standing here right now” and of course, any parent would say that, but that’s the problem: any parent would say that. He follows with: “I don’t pretend to know/The challenges we’re facing/I know there’s no replacing what we’ve lost/And you need time/But I’m not afraid/I know who I married,” and we might as well be on the Dr. Phil show.

Thomas Jefferson (a foppish Desmond Newson, understudying Jordan Donica) then asks, “Can we get back to politics now?” drawing a laugh, but also underscoring that the play handles the political better than the personal. And the play isn’t even completely successful in its politics. Hamilton’s treatment of slavery is perhaps the most puzzling element of the production. Miranda may have thought using African-American actors to play slave owners was enough of a comment, and that’s certainly a better choice than the way that other beloved (but not by me) musical of the American Revolution, 1776 handles it, but the issue recedes so much as to be barely noticeable. (A friend of a friend completely missed that the show dealt with slavery at all. He thought it was purposefully left out.) Jefferson is mildly condemned for it (and Sally Hemings, his slave mistress, is briefly on stage), but if you don’t already know that Washington (a sober and commanding Isaiah Johnson) was a slave owner, you won’t hear anything about it here. It’s as if once Miranda had his big idea, he fudged on other ones. (He may have thought he didn’t need any others.)

I don’t want to minimize what Miranda and his co-presenters have achieved here: In a time when issues of representation and appropriation are pre-eminent, and when spectacle threatens to dwarf talent, people who haven’t ever been to the theater are flocking to see a show that relies on performance, on its cast’s abilities, to deliver an often exhilarating evening. I’m beyond grateful that Hamilton is proving to people that talent is spectacle. And for the actors of color who are portraying characters that, five or six years ago, no one would have ever thought they would be cast as, it must be a life-altering experience. (Among the phenomenal cast, I would single out Isaiah Johnson as George Washington and Pfeiffer as Eliza. And it’s hard not to enjoy Rory O’Malley in the comic-relief role of King George. Michael Luwoye as Hamilton and Joshua Henry as Aaron Burr also do fine work.)

But ultimately, Miranda handles the necessary condensing, editing, and excising inherent in adapting a lengthy biography too obviously, glancing on too many subjects and incidents so that many of them fail to register and we lose any sense of Miranda’s Hamilton as a person who existed. We know his achievements and we know his sorrows, but at the end of the three hours, we still don’t know the man.

Solea Pfeiffer, Emmy Raver-Lampman (understudied by Julia K. Harriman the night I attended), and Amber Iman as the Schuyler sisters. (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Hamilton plays through August 5, 2017 at the SHN Orpheum Theatre, 1192 Market St., San Francisco. Astonishingly, a very small number of tickets are available for most performances. Granted some of these tickets are at the exalted premium level (a whopping $868), but a cursory search found an amazing one-day-notice $197 ticket in the center orchestra, Row J. There is also a same day lottery for $10 tickets. Information about all of this can be found at www.hamilton.shnsf.com.

Wonderful piece. I wasn’t going to read this until mid-August when I’ll be seeing the show, but Mr. Mader conveys its excitement even when sympathetically charting where for him it goes wrong. Now I really can’t wait to join in the post-theatrical discussion.

>

Great commentary. Even if there were faults (which I didn’t feel at the time, and still don’t now) the beauty of pure talent and passion coming together—from the actors to the musicians to the set designers to the writer and beyond—was frankly overwhelming. I sobbed not because it was sad, but because it was so amazing to see what humans can achieve together.